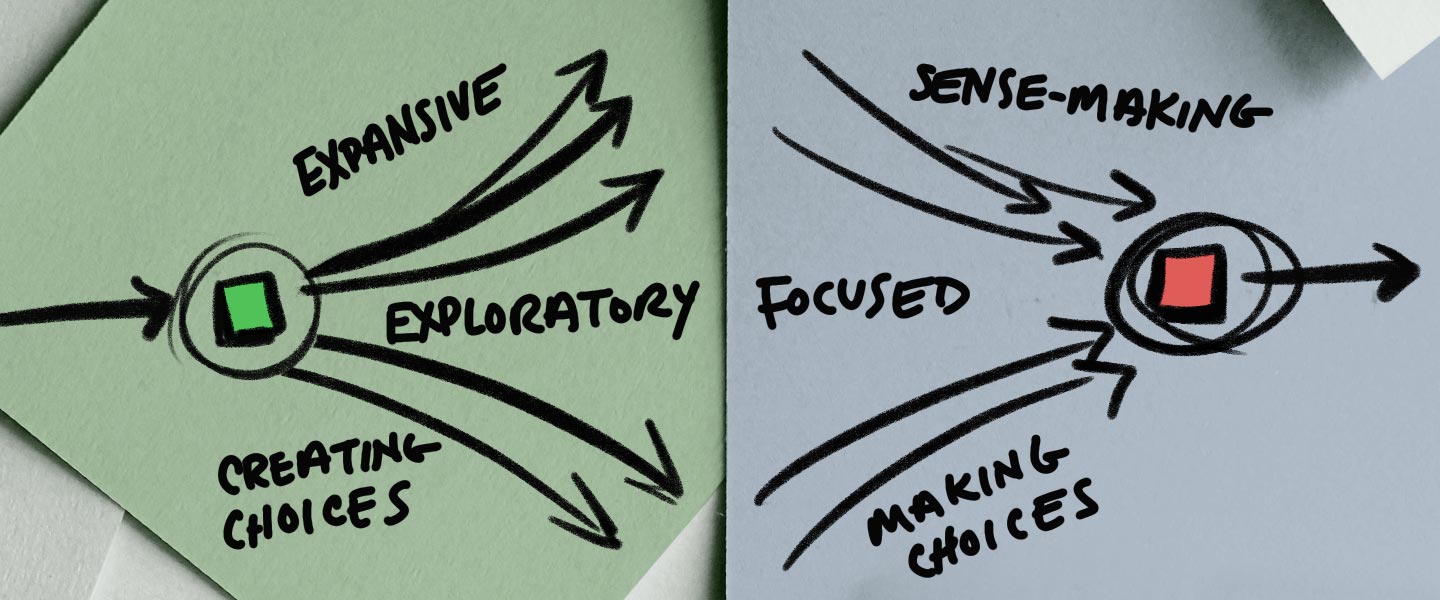

Design thinking is an empathetic, creative, and iterative approach to problem solving. (Oftentimes, people interchange the phrase design thinking with human-centered design. See LUMA’s article The human-centered design “elevator pitch” for more definitions.) The thought process behind this type of problem solving requires iterative cycles of expansive and focused thinking to better understand people and problems, and then develop ideas and solutions. We refer to these cognitive modes as divergent thinking and convergent thinking.

Before we continue, let me define these terms:

- Divergent thinking = An expansive type of thinking that is exploratory and focuses on creating new knowledge or ideas, often thought of as creating choices.

- Convergent thinking = A focused and systematic type of thinking that allows for sensemaking through patterns, priorities and information, often thought of as making choices.

These two distinct types of thinking were coined by the psychologist J.P. Guilford in the 1950s.

While divergent and convergent thinking are opposites, they are both required for complex problem solving. Switching between these modes is often referred to as lateral thinking, which is essential for critical thinking and complex problem solving. For example, jumping between the divergent nature of coming up with new ideas (e.g. brainstorming during Creative Matrix) and then pivoting to select the top ideas to move forward (e.g. Visualize the Vote on the Creative Matrix) is an example of lateral thinking.

Design methods enabling divergent and convergent thinking

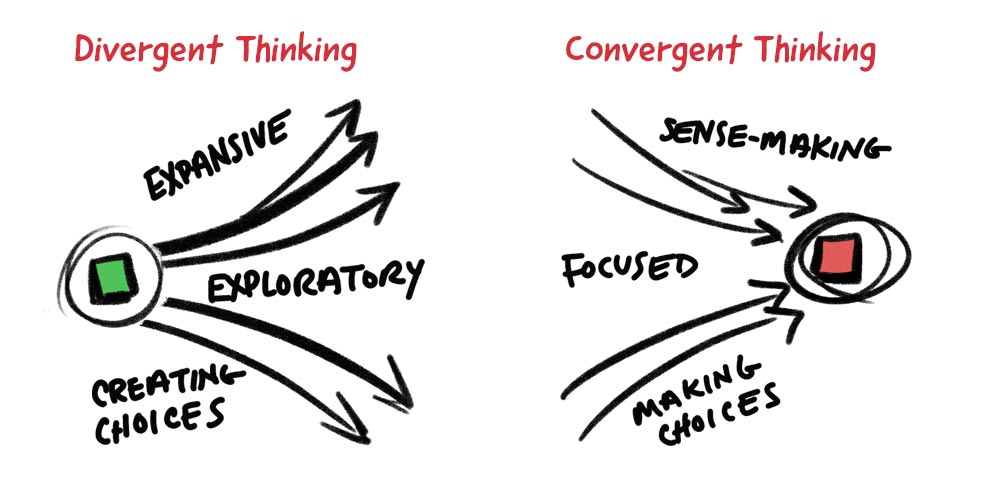

The LUMA System is a curated set of 36 design methods that aid with problem solving. Design methods are short activities that help individuals and teams reach their intended outcome. These methods often guide certain types of thinking. Within a design process, designers use methods at different stages to work towards their intended goals. The nine subcategories (or “neighborhoods”) of the LUMA system can help guide you to choosing an appropriate design method for your situation.

Mostly divergent subcategories

There are some subcategories within the LUMA System that almost exclusively create divergent thinking opportunities. They encourage expansive and/or exploratory thinking, resulting in creating new knowledge or ideas.

- Ethnographic Research (Looking) – These methods center around studying human behavior to uncover needs and insights. As the designer, conducting ethnographic research should result in new knowledge that expands your understanding on the current problem. Your understanding of a problem should expand based on the new information that emerges from the research. Often, you will find more problems to solve, which results in creating more opportunities for innovation.

- Concept Ideation (Making) – These methods are about ideating and developing creative solutions to defined problems. Research supports the notion that you can’t have high-quality ideas without first having a higher quantity of ideas, which aligns with divergent, exploratory thinking. All of these techniques enable creative thinking, brainstorming, and idea generation.

Mostly convergent subcategories

Similarly, there are some subcategories in the LUMA System that almost exclusively enable convergent thinking. These techniques are systematic and focused in their approach, often resulting in decisions about the next steps to take.

- Patterns and Priorities (Understanding) – These methods aid in sense-making and determining next steps. They are logical and focused activities to find patterns in data and identify priorities for how to proceed next. For each of these methods, you need to have some inputs (i.e. data, ideas, tasks) before you can start to make sense of that information in a highly visual and interactive way. These techniques work best in a collaborative manner, so that diverse perspectives can inform decision-making.

- Modeling & Prototyping (Making) – These methods help you envision the future state of a solution. All four techniques help to visualize the chosen concept, making it tangible so that you can communicate it to stakeholders or test with end users. When engaging in modeling and prototyping, you have naturally converged on an immediate direction and then leveraged one or more of these methods to bring that solution to life.

Subcategories that enable both divergent and convergent thinking

Things get more interesting and complicated when we introduce the idea that some subcategories can enable both divergent and convergent thinking in the same method.

- Problem Framing (Understanding) – These methods help you characterize the situation or problem to address. At the onset, these problem-framing methods might look like they should help you converge to one problem statement. However, in practice, many of these techniques actually expand your thinking about the causes and effects (like Problem Tree Analysis) or appropriate scale of a problem (like Abstraction Laddering), thus resulting in divergent thinking during the activity itself. You expand the problem space before ultimately converging on the appropriate statement.

- Evaluative Research (Looking) – These methods assist with examining the usefulness and usability of solutions. On the surface, it can be easy to think that these methods are focused on convergence. However, in practice, these techniques allow for expansive thinking through suggestions about how the solution could be implemented differently. For example, Think-Aloud Testing is a method that is used to test a specific experience or task. On one hand, the testing is continuing to converge towards an ideal solution. On the other hand, the testing can allow new information to emerge (divergent thinking), thus resulting in new ways to approach the solution.

Special cases: things to keep in mind

Primary and secondary purposes for design methods

Design methods can be facilitated in a variety of ways. Sometimes this alters the type of thinking that occurs. Furthermore, our minds can jump between divergent and convergent thinking in a moment, especially if we are well-versed in this approach to problem solving. This momentary “jumping” between thinking modes is essential for problem solving, but it can make it difficult to identify a sole “type” of thinking for each design method. And many design methods can be used to encourage both divergent and convergent thinking. It can be difficult to say that a method does not allow for divergent thinking, since there is always the chance that a method might ignite a part of the brain to think about the problem or solution differently.

I hypothesize that there is likely a primary type of thinking for each method and the possibility for the secondary type of thinking to occur based on the use of the method. For example, a Concept Poster is typically used for convergent thinking to make an idea more concrete and explain it to others, but new ideas may emerge while creating the poster, which means the Concept Poster can also introduce some divergent thinking in terms of developing new ways to approach the problem.

Group activities and co-design

How you use a method — whether individually or in a group — can impact the type of thinking that occurs. When you introduce more people into an activity, this increases the likelihood the group will bounce between divergent and convergent thinking as you learn new information from the people involved in the activity. For example, Affinity Clustering is primarily a convergent thinking activity, where the outcome is clustered (or affinitized) data according to themes and patterns. These clusters help the group determine the next steps and direction for problem solving. This activity is often done as a group, and as such, you may expand your thinking about a problem by discussing the data and re-organizing the clusters. This “new” thinking about the problem results in divergent thinking, even though the final outcome is converged clusters.

Additionally, when engaging in co-design or participatory design activities, the type of thinking will change based on how the person is engaging with the design method. For example, in Participatory Research methods, such at What’s On Your Radar, the researcher is trying to collect new information from the participant (thus, divergent thinking), whereas the participant doing the Radar activity is both reflecting on an experience (divergent thinking) and then prioritizing their reflections and articulating certain items as more or less important than others plotted on the radar diagram (convergent thinking). In these methods, both types of thinking occur during the activity – it just depends on whose perspective you are observing.

Check out the LUMA article on “Co-design: Collaborating with people for better outcomes” to see more examples of LUMA methods for co-design and how they fit into the UK design council double-diamond process.

Switching thinking modes

As mentioned, problem solving requires lateral thinking — moving between divergent and convergent modes. Therefore, it is important to consider how to move between these modes, whether in a method, within a recipe, or between sessions. At LUMA, we refer to a recipe as a specific progression of design methods to solve a challenge. See this article to learn more about recipes.

Switching thinking modes in a method requires you to acknowledge this duality, and then actively switch modes after a prescribed amount of time. Good facilitators know when this is happening and help the participants acknowledge the transition. For example, in Abstraction Laddering you start by exploring the Why’s and the How’s for a specific challenge statement, adding individual sticky notes for each idea (divergent thinking). After a set amount of time, you then shift the activity to discussing the sticky notes, possibly clustering similar themes, and ultimately converging to the desired statement using voting or another prioritization method. As a general best practice, divergent activities can be completed in less time than convergent activities. We usually impose time limits on divergent activities, since time-boxing can often enhance expansive thinking. We usually think about adding more time for convergent activities, since discussion and decision-making can require more time.

Within a recipe, it is valuable to think about what type of thinking each method will enable. If a recipe only engages in one mode of thinking, then you might want to consider adding in another method that allows for the “missing” thinking mode.

If you divide a recipe over multiple sessions with a group of people, then you will also want to think strategically about how you will end each session. As another best practice, sessions that end with a convergent activity can help the participants feel like there is structure to the process and a sense of purpose to the work they completed. If you cannot end on a convergent method, then make sure to clearly define the next steps and how the work in that session will be used moving forward.

Design methods, such as the 36 curated in the LUMA System, are short, well-crafted techniques that encourage forward motion in any design process. While I believe that some methods can encourage both divergent and convergent thinking, the goal of each method will help you identify the primary thinking mode associated with it — noting that there can always be some secondary thinking that occurs.

In the end, human-centered design requires both divergent and convergent thinking to solve complex problems. They are both essential. Deftly navigating moments of divergence and convergence is the key.