Inspired by a belief in universal design literacy and an increasing interest in design thinking, a small team of designers and educators set out on a mission in 2010: develop a single framework of design skills that anyone could learn and apply, regardless of their experience level. We embarked on this journey because we strongly believed what Herb Simon once said: “Everyone designs who devises courses of action aimed at changing existing situations into preferred ones.”

This is the story of how the LUMA System came to be – and how it has inspired and enabled hundreds of thousands of people around the globe, working in all kinds of professions, to harness the power of design and “make things better.”

We began with the assumption that in order to create such a framework, it needed to be based on a foundational set of heuristics (or guiding principles). After some initial research and discussion, we determined that a proper taxonomy of design skills would need to be:

- Based on extensive and thorough research of all known design methods.

- Organized in a way that is relevant and timeless.

- A collection of methods used by many people in various design situations.

- A comprehensible and accessible framework for the masses.

The first guiding principle: Basing our work on extensive and thorough research

Our goal was to help people develop a basic proficiency in design that they could incorporate into their daily work and lives, not necessarily become professional designers. We’re talking about basic skills that are well within the range of everyone’s ability and can be employed to navigate everyday challenges.

This meant we needed to be intentional about checking our biases as professional designers. We wanted to avoid settling on methods that were most familiar to us or simply pick favorites. So we turned to research.

The great thing about research is that it gives you permission to see things in a new light. We agreed to throw out our existing understanding of what we considered to be a design skill or method, and we committed ourselves to seek the answers to these five questions:

- What should we consider a design skill?

- What should be considered a design method?

- How many design skills and methods are there?

- Historically, how have they been organized?

- Has anyone published a set of methods for the general public?

We began our research by conducting an audit to identify and familiarize ourselves with dozens of scholars and practitioners who, over time, had developed a model or published any sort of method collection on design, problem solving, engineering, or creativity.

Our research included everything from classics such as John Chris Jones’ book “Design Methods,” published in 1970, to more recent and well-researched compilations like Vijay Kumar’s book, “101 Design Methods.” We included the methods of Six Sigma and Kaizen; we examined system engineering and design curriculums of top schools like the University of California Berkeley and Carnegie Mellon University; and we spent considerable time familiarizing ourselves with the favored techniques of dozens of creative consultancies like the UK Design Council and IDEO, as well as innovative companies like Steelcase and Procter & Gamble.

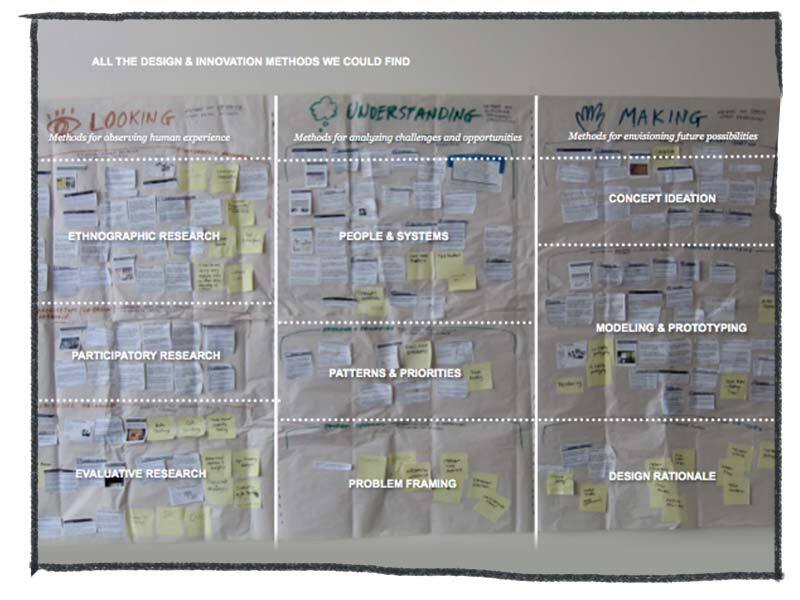

Overall, we uncovered nearly 1,000 distinct design methods. This collection was, to the best of our knowledge, the largest compilation of design methods ever assembled. While many of the methods were variations on a common theme or differed only in name or slight variation in protocol, the sheer size of the list surprised and humbled us. Having conducted this extensive research, we moved to the next question: how might we organize that many design methods?

The second guiding principle: Organizing design methods in a way that is relevant and timeless

In our first phase of work, we noted two primary ways methods historically had been organized: by process or by skill. Our assumption was that our taxonomy should be based on one or the other of these two schemes.

We quickly determined that organizing them by way of a process was suboptimal for several reasons:

- Processes varied from industry to industry.

- People and organizations do not tend to follow one-size-fits-all processes.

- Branded processes are not timeless. They come in and out of vogue.

- Some methods could be used in multiple steps of any process. For example, interviewing as a method could be used at the beginning, middle, and end of any of the design processes we considered.

These insights and our early thumbnail sketches suggested that skills made for a better choice as an organizing principle. As processes tend to be very work-specific, we learned that most people do not believe in a one-size-fits-all process when it comes to design in the broader sense. Therefore, we knew we should avoid organizing methods by way of process, so that they could be used in any process, or in any step of a process. We found organizing methods by skill made sense to professional designers and non-designers alike because it held the promise of a modular and adaptive collection that could be combined and used to take on the different kinds of challenges we run into when trying to design.

Now, the next question emerged: What are these essential design skills?

Any good researcher will tell you that answers to questions reside within the data you collect. These nearly 1,000 methods represented a rich set of data that afforded us the opportunity to build a taxonomy from the ground up, rather than rely on preconceived notions about what we had been taught was a design skill. Our hypothesis was that if we carefully compared and contrasted these methods, a unifying principle would naturally emerge. So, we began to employ one of these methods, an activity called Affinity Clustering, to see what the data would tell us.

After months of study and deliberation, we discovered that all of these methods could be grouped into three meta-skills we believe everyone can relate to:

- Looking: methods for observing human experience by watching people and listening to them.

- Understanding: methods for analysing and synthesizing information, uncovering insights, and framing problems.

- Making: methods for envisioning future possibilities through concept ideation, modeling, and prototyping.

Upon further examination, we realized that the methods under each of these three categories naturally organized themselves into nine subcategories.

Looking subcategories: Ethnographic Research; Participatory Research; Evaluative Research

Understanding subcategories: People and Systems; Patterns and Priorities; Problem Framing

Making subcategories: Concept Ideation; Modeling and Prototyping; Design Rationale

Grouping the ways that people go about looking, understanding, and making helped us understand each practice in more detail. These nine subcategories gave our taxonomy some much-needed structure and transformed it into a more comprehensive approach to design.

Sometimes we find it helpful to think about these subcategories as neighborhoods. We encourage people to “visit every neighborhood,” so to speak, as a way to learn the methods. Another helpful trick is to “get to know the neighbors” when you are looking for a new method that serves a similar objective, because they are grouped by purpose.

The third guiding principle: The collection of methods must be useful to many people in various design situations

We had arrived at a trustworthy taxonomy of design skills, one not influenced by our own biases or current trends or practices, but rather, from a careful examination of the nearly 1,000 design methods we had gathered. The next step was to identify the most essential methods — those that would serve the goal of propagating design literacy.

After some brief deliberation, the answer became clear: it would need to be the fewest number of distinct methods possible — enough to account for a wide variety of applications, but not so many as to be unwieldy. According to our taxonomy, the answer was somewhere between nine (one method for each of the 9 subcategories) and the nearly 1,000 we had analyzed. We had quite a bit of trimming to do!

We had no way of knowing how often each of these methods had ever been used. Nor did it make sense to conduct a survey that asked people to name their go-to methods because of the sheer number of methods we’d identified and the lack of available data on them. And here again, we needed to come up with a way that guarded us against our natural inclination to lean toward our familiar favorites. Each of us, having been professors and/or practitioners of design for a combined 60+ years, was familiar only with a few dozen: a fraction of the methods we had found.

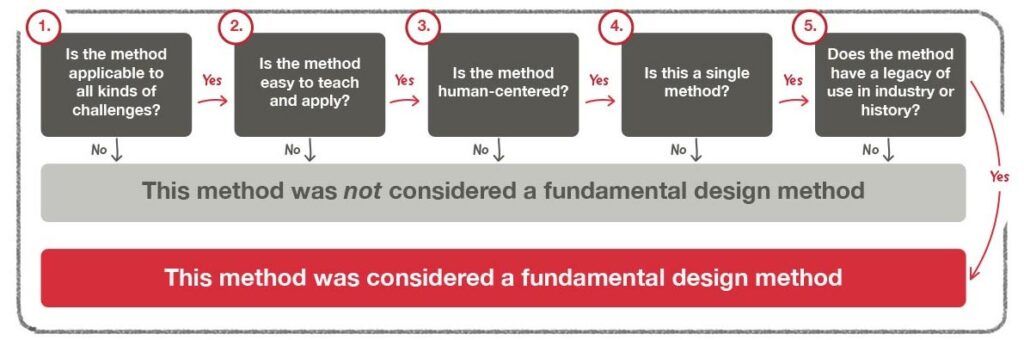

So we chose to create an algorithm — a string of questions or rules that automate reasoning.

Any given method would need to pass five tests:

- Determining the universal applicability of the offering.

- Understanding the ease by which the method could be taught and applied.

- Evaluating the method’s “human-centered” quality.

- Deciding if the method was a discrete single method.

- Examining the method’s legacy and history.

This algorithm allowed us to reduce the number of potential candidate methods from hundreds to dozens.

The fourth guiding principle: The framework should be designed to be comprehensible and accessible by the general public

While creating an algorithm produced a trustworthy subset of methods that we believe represented an essential collection, we still had something of a mess on our hands, with unevenness in each category. For example, there were a dozen ethnographic research techniques still in consideration, but only a handful of design rationale methods. And while we had a good number of methods in our problem framing area, some were so similar that we had to consider if both should be included. When we took a step back and considered what we had, it lacked a clear sense of a whole and instead looked random and complex — the very opposite of what we desired.

In cognitive psychology, there is a technique known as “chunking” in which “individual pieces of information are bound together into a meaningful whole.” It is well-studied and understood among psychologists that when this technique is used, the information presented is more easily remembered than when this same information is presented as individual items. It is also understood that in order for chunking to work, the optimal size of the chunks generally consists of no more than three-to-five items. Phone numbers are a good example.

With this in mind, we made several iterations of the framework and presented each sketch to key stakeholders, who offered us insightful feedback, until we finally arrived at what we called the LUMA System.

You’ll note that the final design is quite orderly. We used color and stacking to delineate the three primary design skills, and we decided in the end to limit the number of methods of each subcategory to four. This was intentional because we wanted to create a picture of the system that was easy to teach, use, and recall.

This is not to say that there aren’t other design methods that we consider to be very good. Note the small ellipses under each subcategory. It was our subtle way of reminding ourselves and our clients that there are more methods, and that this system is not a complete compendium, but an essential, comprehensible, and accessible framework for everyone!

The LUMA System is a modular and adaptive collection of 36 essential design methods, organised into nine design subcategories, which fall under the three primary design skills of looking, understanding, and making. Now, more than ten years later, it still stands as the most practical, flexible, and versatile approach to innovation in the world.

A bright future of working better together

While we can in no way claim that universal design literacy has been achieved, the LUMA System is helping to make progress toward that ideal future state. We always have more to learn, but we are confident that a system configured such as ours is necessary to the propagation of design literacy.

Imagine a world in which hundreds of millions of people have mastered basic design skills so they can frame problems, deeply understand people and situations, pull insights from a complex sea of data, generate unconventional ideas, sketch, build prototypes, test assumptions, and iterate quickly — the hallmarks of good designers.

Imagine a world in which everyone is as competent at looking, understanding, and making as they are at doing arithmetic, simple forms of algebra, and geometry. Imagine that they possess the creative confidence and capability to take on all kinds of opportunities calling for change.

Admittedly, it’s hard to see that future clearly. But I predict that it will be a world in which people enjoy their work more, collaborate more, and tackle more of the world’s problems, big and small, easy and wicked. I can’t help but wonder if that world would be an entirely different place than it is today. And I’m entirely convinced that we can design our way to something better.